Katarzyna Czeczot

Ophelia’s Collective

“Say you? Nay, pray you, mark.“[1] We mark. But only images follow. The one that most often recurs is obviously: “Her clothes spread wide, / And mermaid-like a while they bore her up.“[2] Ophelia drowns. Slowly, softly. Calmly. “Like a creature native and indued / Unto that element.“[3] She drowns as if she was dissolving, undergoing a gentle metamorphosis. And as if she was soon to transform into a “weeping brook.“ Akin to Arethusa from Ovid’s poem: “And dark drops trickled from my whole body. / Wherever I moved my foot, a pool gathered, and moisture dripped from my hair / And faster than I can now tell the tale I turned to liquid.“ Yet, Ophelia’s images never show her transformation into a brook. Floating on the waves, her body preserves its form and never loses its identity.

There is perhaps no other literary figure so frequently represented in visual arts. Therefore, as we read the description of a drowning Ophelia today, a different kind of metamorphosis comes to our mind and compels us to perceive her fall into the “weeping brook” as a moment of immobilisation. Ophelia’s body will never reach the “muddy death.“ It is stopped on the water surface and becomes arrested in the image. Ophelia transforms into an aesthetic object. And the sense of this transformation does not boil down to the simple fact of her becoming an object of painterly representations. Her metamorphosis into an image precedes all individual images. It marks a separation between what can be shown and what should remain unseen. Behold a woman’s body whose beauty is revealed, on the one hand, by flowers that bear resemblance to it, and on the other hand – by a thin layer of water that closes in on the drowned woman akin to a glass showcase. Ophelia’s representations may actually be treated as second-degree representations, meta-images, which capture the very principles of representation. The focus here is essentially on a metamorphosis that puts an end to all metamorphoses. A metamorphosis in which water, instead of suddenly gushing out, oozing secretively, dissolving, begins to preserve the body. The main role of water in traditional representations of Ophelia is to veil the corpse, conceal the scandal of decomposition. Remove from sight the “muddy death“ that undergoes a constant metamorphosis.

Zorka Wollny describes her work Ophelias. Iconography of Madness in terms of “theatre found footage.“ Its components are fragments of eleven different stagings of Hamlet showed in Poland between 1960 and 2012. The artist invited to collaboration the actresses who had played the role of Ophelia in those spectacles. They were asked to act out selected scenes once again. Having initially worked separately with each of them, Wollny then went on to weave the individual performances into a spectacle that has its own independent dramaturgy and whose meaning is more than just the sum of the meanings of the fragments. Ophelias premiered at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in a spacious exhibition hall without a clear division into the stage and the audience. The actresses in different parts of the hall take turns to speak. Time and again one can hear the lament after the lover’s death, the Saint Valentine song, mysterious maxims, explanations concerning the flowers handed out by the characters. We soon realise that almost all the lines – although originating from various translations of Shakespeare’s play – come from a single scene. All actresses bar one are acting out the scene of madness. This repetitiveness produces an effect akin to the metamorphosis that can be deciphered in the description of Ophelia’s death. A looped Ophelia resembles the one who is imprisoned in an image. “Say you? Nay, pray you, mark.“ We mark. And in Wollny’s spectacle, we listen to a story about the impossibility of going beyond the frames of a certain imposed scenario. Her Ophelias are women caught in a trap, locked in a vicious circle. In images. In two types of images, precisely speaking.

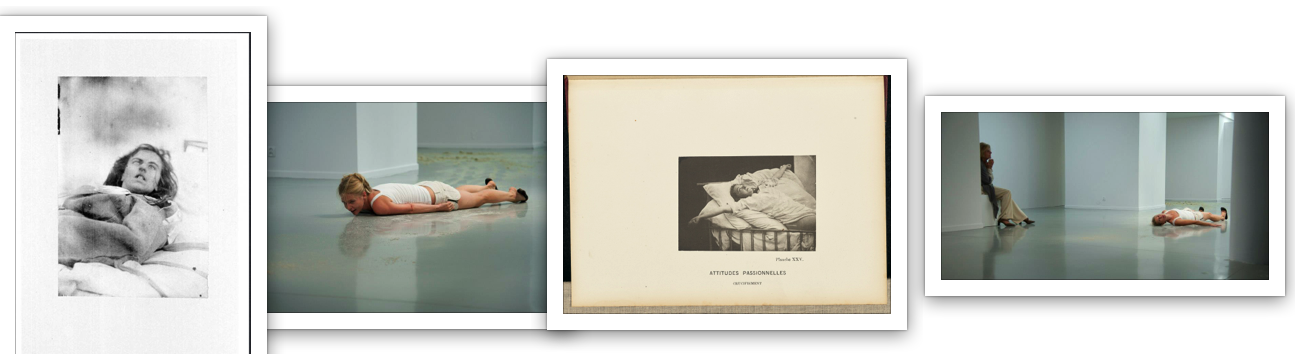

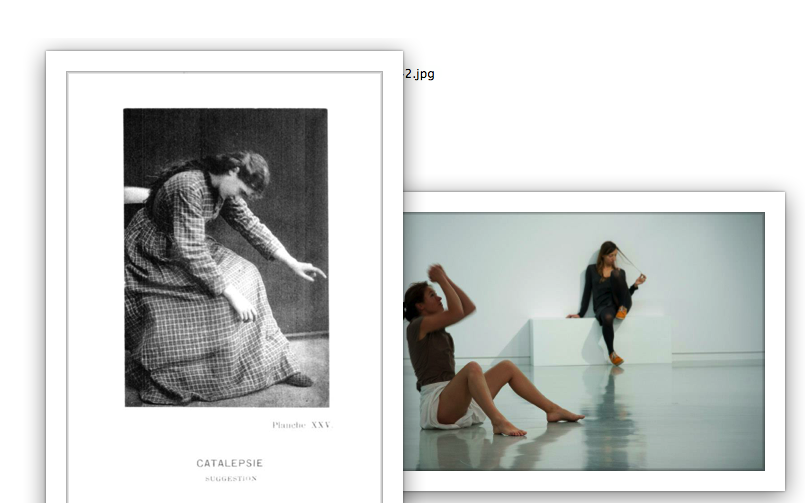

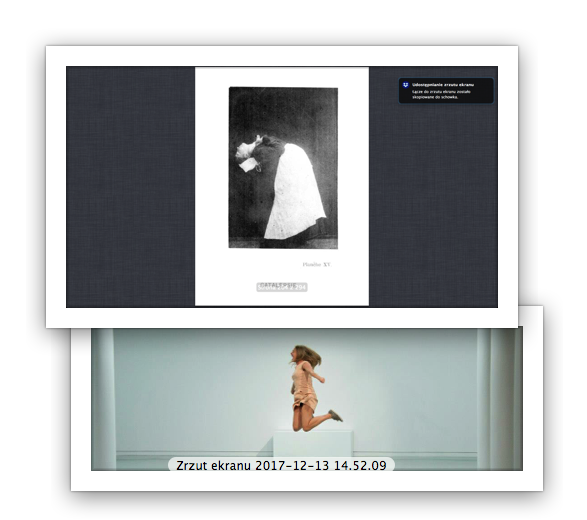

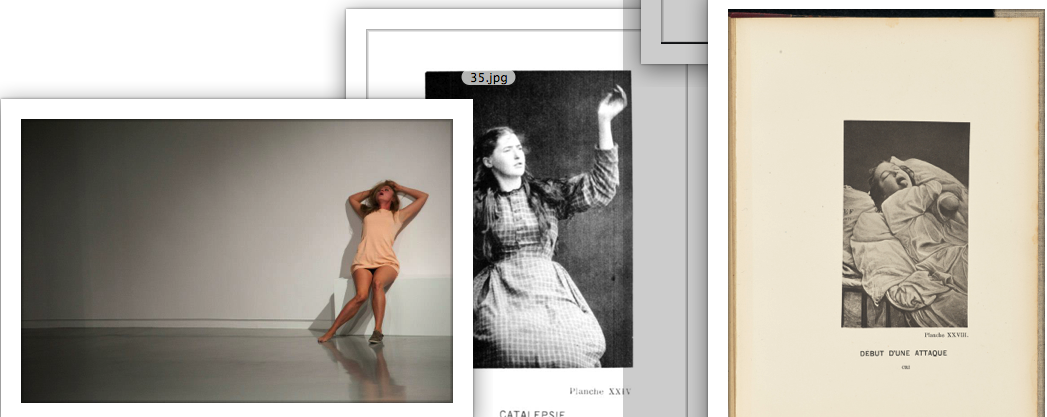

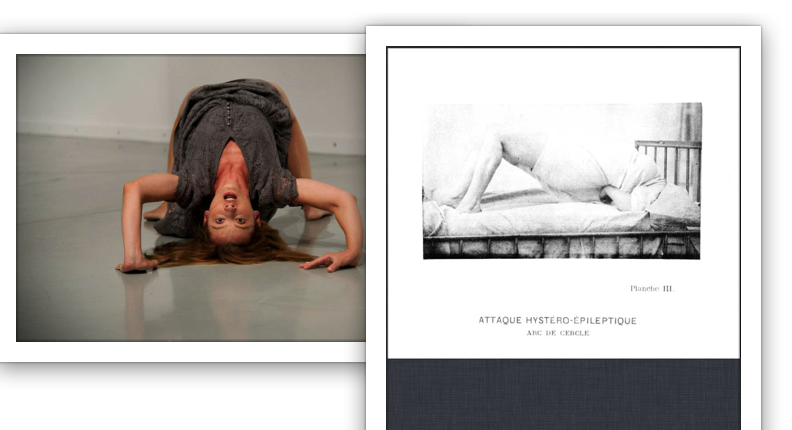

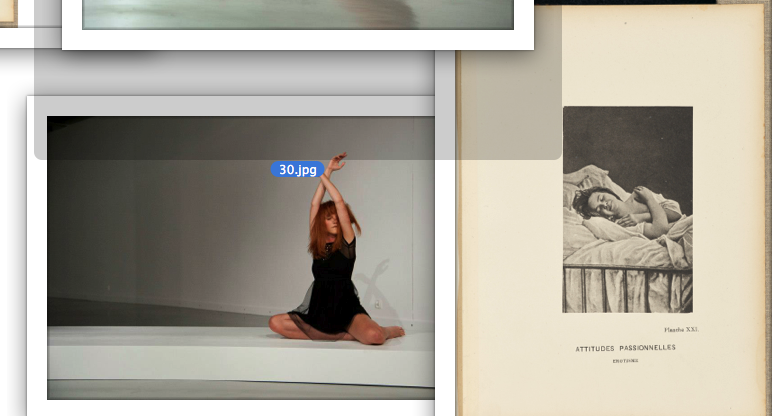

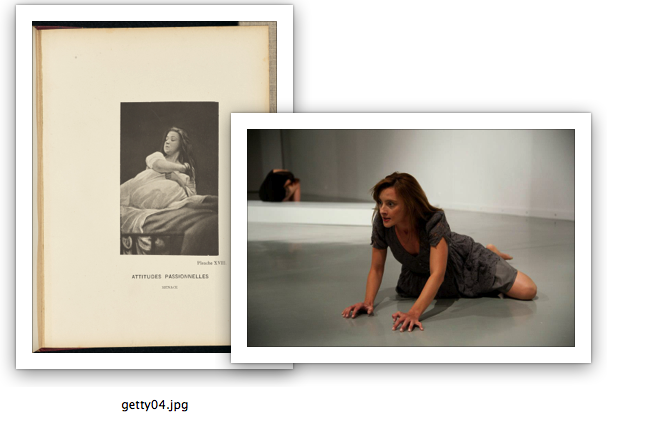

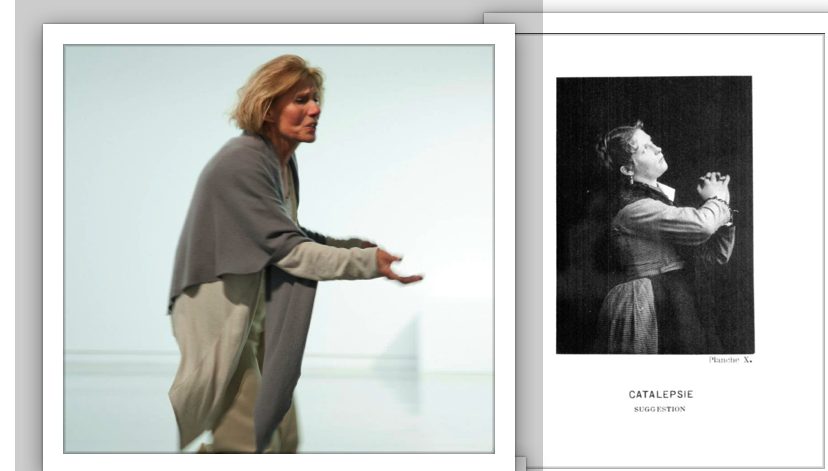

One of these types is represented, of course, by the photographs of Charcot’s hysterics captured in the midst of an attack. Those images are difficult to get rid of as we watch Wollny’s Ophelias. What strengthens this connection is the subtitle of the work – Iconography of Madness, which brings to mind Jean-Martin Charcot’s several-volume Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière.[4] Addressing both this study and Charcot’s series of lectures that served as its basis and featured demonstrations of attacks of hysteria suffered by women patients of the Salpêtrière hospital, Georges Didi-Huberman will later say that it was a time of “an extraordinary proliferation of images.“[5] The stake involved, as the scholar underlines, was obviously knowledge about nervous illnesses. Yet, Charcot turned photography into a tool to explore those illnesses. Forming the Salpêtrière iconography, the photographs by Paul Regnard (who was, notably, a doctor himself) depict an attack of hysteria as a series of poses assumed by women patients (Didi-Huberman points out that none of the several thousand photographs features a man!). The Ophelias played by the actresses invited by Zorka Wollny to collaborate on her work clearly refer to that very imagery. As they scream, roll their eyes, perform obscene movements, some of them look as if they lost control over their own bodies. Others assume dramatic poses and throw mad glances at us, thus making an additional reference to Tony-Robert Fleury’s painting that depicts a Salpêtrière patient from the times of Charcot’s predecessor – Philippe Pinel, portrayed by the painter as he releases his patients from chains. The collection of gestures that Wollny’s Ophelias develop is a spectacle that indeed implements the idea of a “pathology museum,“ to use Charcot’s own term.[6] This similarity is additionally underscored by the white walls of the exhibition space. Wollny re-creates in a certain way the atmosphere of the 19th century, when “tours“ of mental asylums were in vogue. Yet, the images of mad women known from the history of medical culture are merely one of the kinds of images forming this strange picture that Iconography of Madness directed by Zorka Wollny becomes. The other type embraces the images of Flora referred to in Shakespeare’s scene of Ophelia’s madness.

Such images provide the topic of an article by Bridget Gellert Lyons. Reflecting on the visual sources of the scene of madness, the scholar evokes the mythological figure of Flora, who is often depicted handing out flowers. Botticelli’s Primavera also portrays her as the nymph Chloris. She transforms into a goddess of fertility, growth, love and ecstasy after being abducted and raped by Zephyrus, as described by Ovid in Metamorphoses. However, another version of this myth also exists which derives its origins from Plutarch. Flora appears here as a prostitute in Rome who abandons her profession, marries into wealth and goes down in history owing to her wish, expressed in her last will, that her wealth be used to organise a yearly public festivity on the date of her birthday.

What emerges from the juxtaposition of these two versions of Flora is, on the one hand, the opposition between the world of nature and the urban space, whereas on the other hand – two different concepts of female sexuality. The first connects ecstasy with the advent of spring, sprouting, budding, blossoming, a cyclical revival. The principal reference point for the second concept is the market which transforms sexuality into a commodity. It is noteworthy that those two images were absorbed by Renaissance culture. Beside Botticelli’s Primavera there are also paintings by Titian and Palma Vecchio in which Flora, wearing a robe that reveals her breast, is clearly supposed to bring to mind a courtesan. Yet, Gellert Lyons distinguishes yet another type of representations. It comprises images that do not continue any of the lines determined by Ovid and Plutarch, but instead “exploited the incongruity between the two versions of the Flora legend.“[7] They include canvasses by Jan Massijs and Guido Reni that reveal the tension between the ritualistic and the market-driven understanding of women’s sexuality.[8]

The two versions of the legend of Flora also pass through to Hamlet and their incongruity lays bare the paradoxical manner in which iconographic references function in the drama. Shakespeare does not employ traditional motifs in order the clarify the meaning of individual scenes. Iconographic tradition does not appear in his work as an element of a legible code and never translates into cognitive axioms to which Erwin Panofsky wanted to reduce it. It is impossible to discern a codified sign system amidst the conventions of representation evoked in Hamlet. Gellert Lyons argues that their presence always causes a kind of dissonance; that there is an essential divergence between the concept and the image. Apart from the example of Ophelia handing out flowers, the scholar also quotes a different moment of such a rupture. It is a scene that incorporates a characteristic Shakespearean device – theatre within the theatre. The role of directors is played by the King of Denmark and Polonius. “Ophelia, walk you here.“[9] That is how the “two fathers“ resolve to discover the character of Hamlet’s madness. Observing from hiding the course of prince’s meeting with Ophelia, they intend to exclude the possibility of madness caused by love. Initiated into their plan and left in an appropriate place, Ophelia is given a book and instructed: “Read on this book / That show of such an exercise may color / Your loneliness (…) ‘Tis too much proved, that with devotion’s visage / And pious action we do sugar o’er / The devil himself.“[10]

Gellert Lyons points out that the book given to Ophelia remains undefined, and yet it functions as an attribute of a pious woman. It is possible due to a reference – obvious for Shakespeare – to the iconography of the Annunciation. It is in the visions of the Annunciation that Virgin Mary is usually portrayed with a book. Yet, Shakespeare also here prevents a situation in which a specific convention of representation determines in a simple way the sense of the scene itself. For one cannot interpret the image of solitary Ophelia immersed in reading a book as an emblem of innocence and virginity. Her concentration is staged. “Her father and myself (lawful espials) / Will so bestow ourselves that, seeing unseen, / We may of their encounter frankly judge.“[11] Ophelia’s prayer cannot be understood only as a set of conventions. And, in this sense, the analysis pursued by Gellert Lyons proves the failure of Panofsky’s project, while her study finds a perfect supplement with Didi-Huberman’s book Confronting Images. Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, which delivers the following commentary on Panofsky’s iconology: “Iconology, then, delivered up all images to the tyranny of the concept, of definition, and, ultimately, of the nameable and the legible: the legible understood as a synthetic, iconological operation, whereby invisible ‘themes,’ invisible ‘general and essential tendencies of the human mind’ – invisible concepts or Ideas – are ‘translated’ into the realm of the visible (the clear and distinct appearance of Panofsky’s ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ meanings).”[12] The Sheakespearean images of Ophelia do not surrender to this tyranny. “Say you? Nay, pray you.“

It is this very dissonance, this rupture in the scene of madness, in the gesture of Ophelia handing out flowers, that allows us to fully comprehend the meaning of this character for Feminist critique. In Shakespeare’s piece, the combination of the incongruent images of Flora expresses the conflict between two significantly different projects of sexual ethics. Yet, let us remark that Shakespeare renders this opposition between the divine and commodified vision of female sexuality in other scenes of the drama. The moralising preaching offered to Ophelia by Laertes does indeed include the warning that the girl should protect her “chaste treasure.“[13] And it is the mythological context that allows us to notice that the call to exercise restraint which Ophelia hears everywhere refers to the categories of the market. Laertes’ argument frames virginity as capital that needs to be invested wisely. The same logic hides in the song of Saint Valentine. It tells the story of a girl who carelessly squandered her treasure. She faces a punishment for her lack of restraint. Abandoned by the lover who breaks the promise of a marriage, she hears from him: “So would I ha’ done, by yonder sun, / An thou hadst not come to my bed.”

In the project Ophelias. Iconography of Madness Zorka Wollny repeats a procedure that she had already used in an earlier video work from 2008. On that occasion, the artist collaborated with Marta Ojrzyńska, an actress from the Stary Theatre in Cracow who performed the main role of the eponymous Lulu in a spectacle directed by Michał Borczuch (based on a play by Frank Wedekind), and asked her to play her role once again – this time alone, without other actors, and not on stage but at her own apartment. The result is a 48-minute record of a peculiar monodrama in which Ojrzyńska lingers around empty rooms while gesticulating lively and uttering torn monologues which sound grotesque and absurd in that void space. Akin to Ophelias, the work shows the impossibility of exiting the role. Insofar as during the first minutes of the film we may still get the impression of watching an actress preparing for a role, further takes compel us to suspect that the role has taken control of the actress.

I have written that a similar kind of imprisonment in the role is perceptible in Wollny’s Ophelias. That the reference to the Salpêtrière iconography, the “re-creation“ of Charcot’s “pathology museum“ turns Ophelia into a figure who proves that revolting women are condemned to the role of lunatics. At the same time, however, the persistent returns to the scene of madness in Wollny’s spectacle, the focus on the ambiguity of Ophelia’s character and the conflict between two visions of female sexuality lead to a certain rupture. The impression of imminence, of the eternal return of the same, disappears. Ophelia handing out flowers, Ophelia singing lewd songs, an innocent Ophelia and an obscene Ophelia is not only a victim of patriarchal sexual ethics. The vicious circle becomes interrupted. Wollny compels us to treat Ophelia as an unmasker of the double sexual ethics de rigeur at the court. Her madness, in turn, rises to the rank of a protest against the perception of female sexuality in market categories and the objectification of the female body.

Let us return for a moment to the dress stretched on water akin to a mermaid’s tail. It seems that the story of Ophelia transformed into an image is a paradigmatic one. Image functions here a tool to discipline women’s revolt. It corresponds to the walls of an attic where a rebel gets locked if she opposes male oppression – to refer to the famous figure created by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar. For is it not the same model of the story that is implemented by Louise Augustine Gleizes captured in an ecstatic pose, Charcot’s most famous patient? Here is a woman brought up in a bourgeois value system, who was denied the right to education, to love and to bliss; a woman for whom the only available form of revolt is the scandal of the body bent to form a hysterical bow, and who witnesses attempts to suppress her revolt by transforming it into a medical case and inserting it amongst hundreds of photographs that depict “nervous disorders.” Yet another version of the story could involve female participants of the French revolution. Initially depicted as mad megaeras, they are replaced in the course of time with allegorical images of Liberty. Evoking the works of Maurice Agulhon, Maria Janion writes about the symbolic power of this holy image, which consists in: “distancing the real woman from participation in public life; depriving her of subjectivity both in economic and political terms: exclusion from social discourse and social practice.”[14]

Jola Janiczak’s drama Stateswomen, Sluts of Revolution, or the Learned Ladies (Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy), which tells the stories of women participating in the French Revolution, including Théroigne de Méricourt, a courtesan who became a revolutionary, at a certain point shifts the accents in order to reveal a similarity between the 18th century politically-engaged women and contemporary actresses who play the roles of revolutionaries. At a certain moment, one of them delivers the symptomatic line: “If we had treated ourselves seriously, we wouldn’t have chosen a profession that situates us in the apple of the eye, which compels us to show that we are liberating ourselves and taking others along with us, which focusses like in a lens and reproduces all the models that have been imposed on us for ages.” As a work largely devoted to the iconic status of Ophelia, Wollny’s spectacle addresses a very similar problem. The artist asks a question about the emancipatory potential of a woman situated in the apple of the eye. But also – akin to Janiczak – deals with the similarity between Ophelia and the actresses who play her role. This juxtaposition is very expressive and has a strong justification. Let us repeat the scene discussed, amongst other figures, by Gellert Lyons: “Ophelia, walk you here / Read on this book / That show of such an exercise may color / Your loneliness (…) ‘Tis too much proved, that with devotion’s visage / And pious action we do sugar o’er / The devil himself.” The title of Margaret Atwood’s famous novel The Edible Woman brings to mind an expression that recapitulates well a certain collection of visions amongst which the figure of Ophelia sits: a woman to be looked at. Does it not express well the status of an actress? What way out of “a profession that situates us in the apple of the eye” does Wollny’s spectacle propose? It seems that this way out consists in establishing a collective of Ophelias, which becomes here a collective of actresses at the same time.

“Say you? Nay, pray you.” “We will tell you” – say the Ophelias from Wollny’s spectacle and say the actresses who play their roles. The multiplication of the role which heavily differentiates the artist’s project from her earlier film Lulu; dividing the same script into different variants; multiplying the figure – it all has a crucial meaning. The idea behind such an undertaking was poignantly summarised by Hito Steyerl, who envisions a world in which “as people are increasingly makers of images – and not their objects or subjects – they are perhaps also increasingly aware that the people might happen by jointly making an image and not by being represented in one.”[15] Wollny’s Ophelias speak in order to make it possible for the actresses to speak, and the experience of each of them is presented here as essentially different. Beyond doubt it is partly a question of the fact that the images that form this iconography of madness – sometimes through significant and sometimes through very minute shifts of tone – generate a review of theatre conventions, a kind of condensed history of acting, which may be presented non-chronologically and in snapshots, but is nevertheless accessible and quite expressive. Yet, at the same time, this review consists in histories of specific and material bodies. The collective of the Ophelias and the actresses is not founded on the unification of experience. It is a community that exposes itself to a gaze in order to express its own multiplicity. And thus, in a collective effort “the image can devour the Idea at the very moment the Idea thinks it can absorb the image.”[16]

[1] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed. Cedric Watts (London: Wordsworth, 1992), p. 119.

[2] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, p. 131.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Entirely digitised and made available at: http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/subset.html?name=collections&id=charcot_icono_salpetriere; http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/subset.html?name=collections&id=charcot_nouv_icono_salpetriere. Access: 24 November 2017.

[5] Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, trans. by Alisa Hartz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), p. 4.

[6] Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, p. 17.

[7] Bridget Gellert Lyons, The Iconography of Ophelia, ELH 44, no. 1 (1977), p. 65.

[8] Bridget Gellert Lyons, p. 64–65.

[9] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, p. 86.

[10] Ibid.

[11] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, p. 85.

[12] Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, trans. by John Goodman (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press), p. 122.

[13] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, p. 52.

[14] Maria Janion, Kobiety i duch inności (Warsaw: Sic!, 1996), p. 41–42.

[15] Hito Steyerl, The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation, e-flux Journal #32, February 2012.

[16] Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, p. 125.

Katarzyna Czeczot – assistant professor in the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Her interests include representations of madness in modern European culture, cultural contexts of psychiatry and feminist critique. Author of articles devoted to romantic and contemporary literature and visual arts. Co-editor of “Encyclopedia Gender” (2014). Author of the book “Ophelism. Romantic appropriations, feminist interventions” (2016).